Last year, I gave a talk titled “The Anatomy of Machine Learning Teamwork” at BigData/AI Toronto and the Vector Institute. Leading teams is contextual, and this post is specific to managing an applied research team with a focus on natural language processing, particularly within the application of fictional stories. Our successes included creating a novel and monetizable product offering which delighted users. Asides for commercializing our research, the team published a paper, accepted at EMNLP 2019. This post covers team composition, how the team is organized, and collaborate together. Part 1 covers team composition.

Functional, component organizational structures work well, if the thing you are trying to optimize is collaboration within a particular function. For example, engineers can be working on interesting, hard technical problems. Data scientists can be in their corner hypothesizing, and stirring that data until they find a model that outperforms their last. Meanwhile, your product team is plotting what your next big feature or function is; and trying to figure out how to get everyone aligned around working on it.

The overhead of communication was getting higher as the company grew, and often coordination happened amongst managers. This means the people doing the work didn’t always understand the complete picture of why doing this thing was moving the company forward. Across the organization, we weren’t maximizing the benefit of diversity of thought, leading to not understanding the problem as well as we could, and also leading to suboptimal solutions. Even within engineering itself, it leads to a slew of headaches as client engineers tried to integrate with APIs built by another engineering team which is operating under their independent timeline and on top of incomplete requirements. Don’t even get me started with the friction of releasing machine learning models into production.

Over time, we transformed ourselves into cross-functional, feature teams. Each team gets to own a mission, empowered to frame the macro and micro problems that fit within that mandate, and own the solution to how to address the problems. Imagine being able to control the full (or at least, most of the) lifecycle of building a product within your team! Everyone in the team is to collaborate on ideation and execution, to be able to take in perspectives outside of their own. Together, we design, build, and maintain a large scale distributed system that serves the needs of tens-of-millions of people globally. We hold each other accountable for continuous improvement not only for our systems, but arguably more important, ourselves.

The data scientists spend their time applying research papers to our data moat, coming up with new approaches, as well as tailoring solutions that fit the needs of our business. They come up with a variety of creative ways to apply our data to solve real problems. And finally, they are often our strongest advocate for new types of data we need to collect.

The engineers take on the full stack of software engineering - from the moment a reader opens a story on their phone, to the APIs that fetches the text from our cloud provider, optimized behind our content delivery networks and internal caching layer, to ingesting real-time feedback, which gets routed to our message broker, into our data lake, with a mix of real-time and batch jobs that enable the rest of our company to easily work with, interpret and manage our data into insights and actionable decisions.

Our product manager meanwhile, is talking to our users, figuring out their needs, understand how our product add value in their lives, identify gaps where we’re under-serving them. It is also crucial for us to understand our potential market, and any competitors that might be already in that space. Internally by talking to our stakeholders, we ensure that the work we are doing feeds back to the vision of where our company wants to be in 5 to 10 years.

Had I stayed on to grow the team further, I would have advocated for a product designer, someone dedicated to visual communication, human-centered experiences, and user research. Further along, I would have advocated for subject matter experts in our domain - in this case, someone with a background in writing, editing, and linguistics.

Two Questions

As a team, we face these questions repeatedly:

Will users find value in it? Nobody wants to waste time building something that nobody will use or find value in.

Is it possible to build? Software projects can be risky, and there are plenty of things that are possible, but hard under tight constraints. When you introduce machine learning into this mix, some things are not only hard, but impossible. There is a tonne of excitement right now of what AI/ML/DL can do, but we need to separate reality from hype.

Dual Track Agile provides a framework for two phases: discovery and delivery. The team generally participates in both tracks. In the discovery phase, we are trying to learn what users value. In the delivery phase, we are optimizing for scale and quality.

Discovery for ML Teams

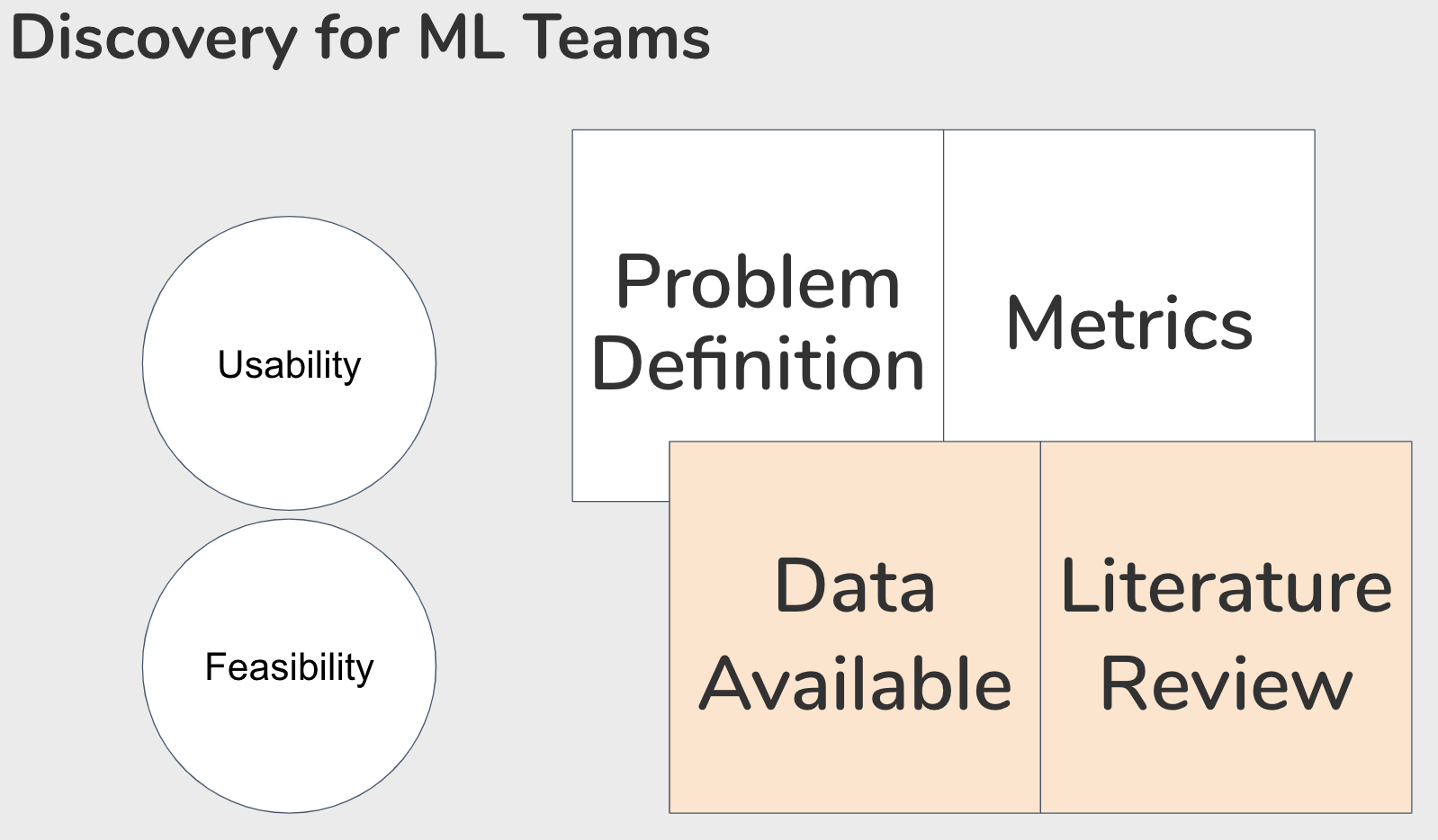

This mental model provides a baseline for all teams, regardless if they have data practitioners on them or not, as they share many characteristics. Take for example, in any situation we always start with a problem. As we understand the problem better, we can also devise goals and metrics to target. The outcome of the discovery phase involves taking a series of divergent discoveries that converge into iterable solutions that keep usability and feasibility in mind. After we deploy the new or enhanced feature to the user, the discovery track will take new learnings from the delivery phase.

A major differentiator to how machine learning teams will differ from traditional software teams is the need to thoroughly examine the data available, as well as go through a literature review of existing solutions. These are skills that uniquely your data scientists (and engineers) will bring to your ML teams. Over time, you might find that as you’re years into the ML journey that you’re starting to exhaust your sources of data – discovery is also a good time to identify what new sources of data you might want to design into your product, or to acquire through other means.

Delivery for ML Teams

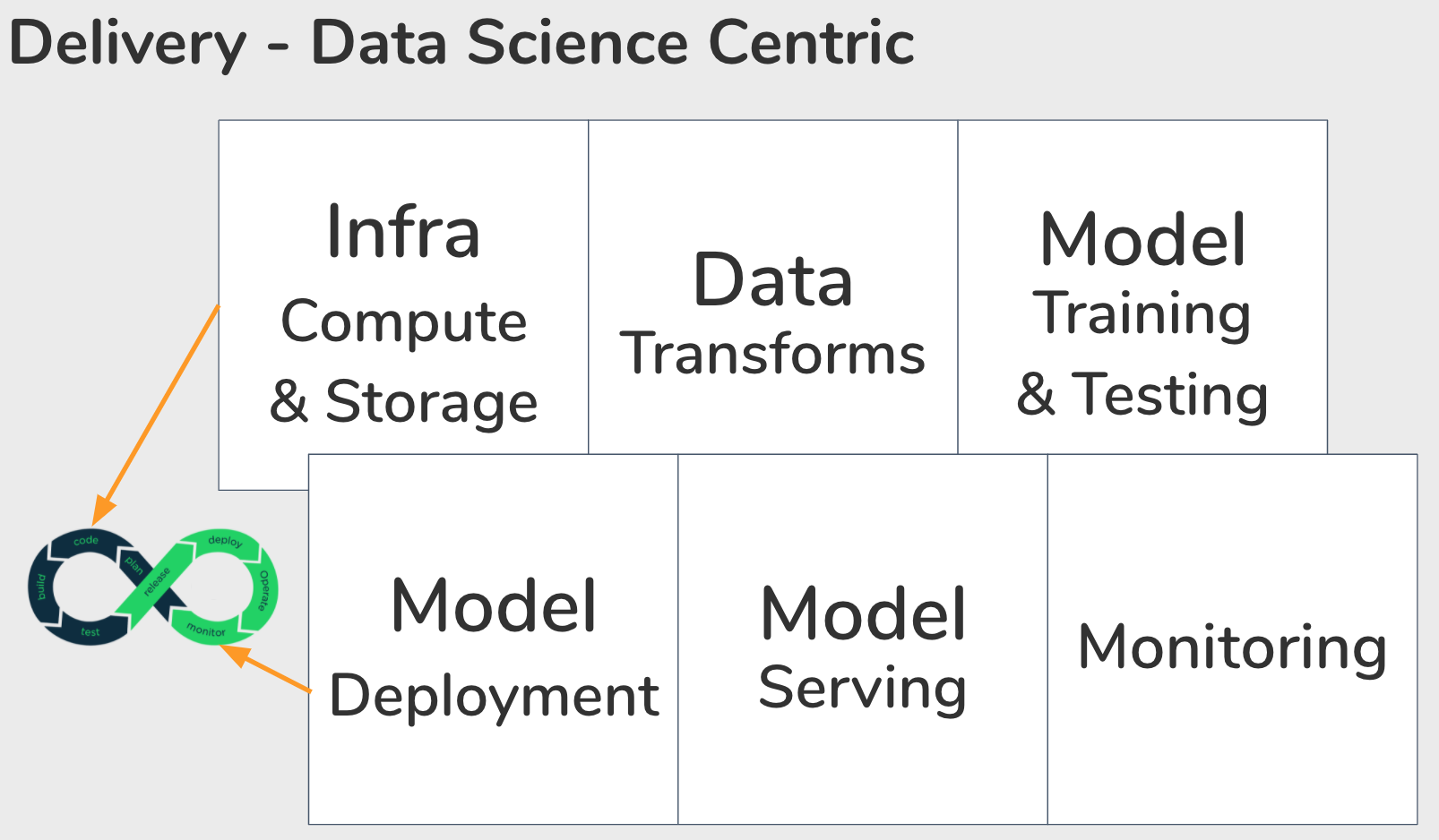

The delivery phase follows a similar lifecycle as traditional software. At this point, your team has identified a need to address, and have decided the measure of success. They have an educated guess that the solution they’ve come up with, is both deliverable within a foreseeable timeline as well as a best guess on the impact it’ll make. With a plan in hand, your team starts coding, building, and testing a solution. Assuming you were able to develop a model that fits, then you deploy, scale, and monitor your solution in production.

I am going to zoom into how delivery differs when you have data scientists at your company. Data scientists across the industry will have varying levels of scope. The joy of working at a smaller organization (in my opinion) is being able to take ownership of the end-to-end lifecycle of your work. In this case, our data scientists pick an environment they want to prototype in. This will depend on how data and compute hungry the model is. Afterwards, data scientists take time back and forth to cleanse, transform, aggregate data into useful signals for their model. Whilst taking a variety of approaches, and evaluating them based on the metrics you decided on in discovery. One of the hardest things to accept about the nature of data science work is that it is risky, and the possibility of failing is very real. The important thing here to be able to identify when to cut your losses, and be courageous to end it. With every failure, you need to conduct an error analysis so that you can try to at least understand how and why it failed. This is a crucial step else your organization is not going to be able to build upon its learnings, and develop an intuition for what might work (or not) moving forwards. Many failed attempts later, you might find one that we’re satisfied with. Or conclude that there are diminishing returns for your effort. Or that it is not possible to push the performance of your model any further at the current moment. But if you are so lucky to make it out of the development phase, you can finally start thinking about deploying this model into production, periodically re-training your model, serving, and continuous monitoring the performance of your model to detect any shifts in the distribution of data you’re expecting.